There is a saying amongst Cruisers, “There are those who admit to having run aground, and then there are liars!”

Maiatla under full sail

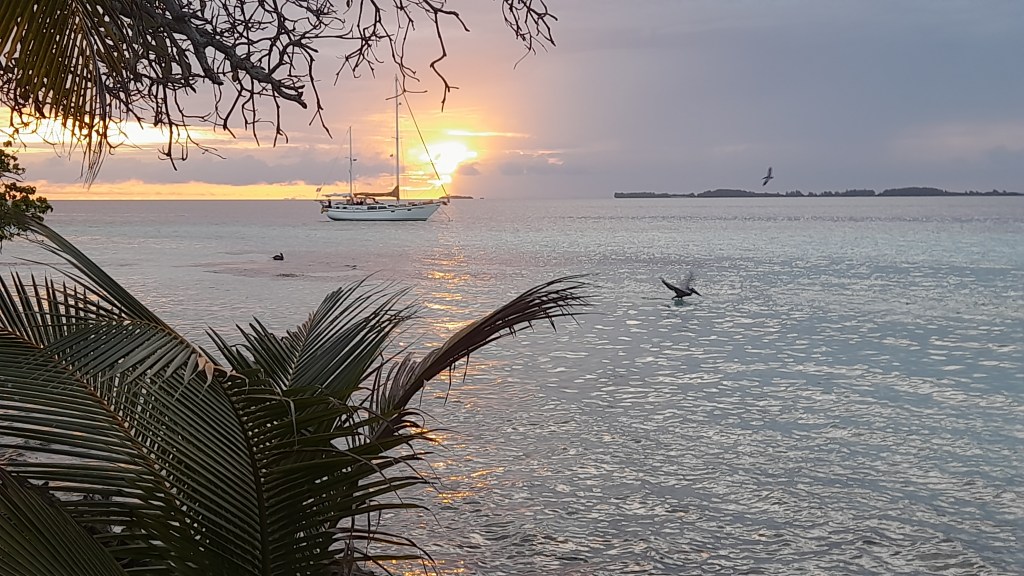

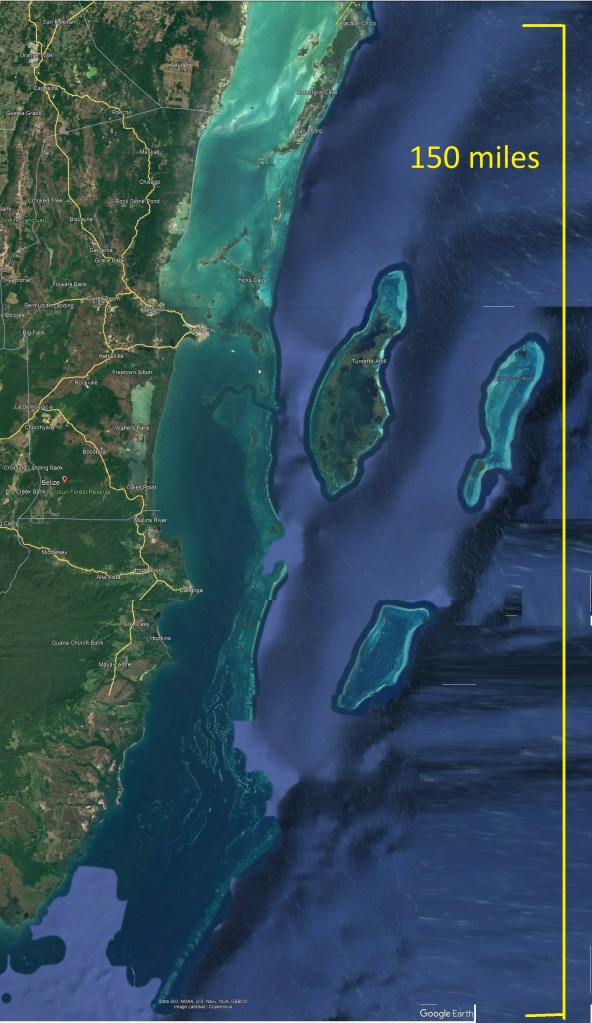

The offshore islands of Belize are a natural wonder to be sure with its hundreds of beautiful islands and white sand beaches. The water is blue-sky clear and is teeming with marine life and what makes it all possible is the coral barrier reef, the second longest in the world next to Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

Belize, 150 mile long Barrier Reef and three coral atolls.

It’s an increasable diving and cruising ground for sailors with its countless anchorages and rustic beachside bars and restaurants. But despite all that it has to offer, this mecca has a dark, hidden side which come in the form of poorly charted reefs and shifting sand bars which often migrate during hurricane season.

Bommies, hundreds if not thousands of small coral heads are scattered about, often hidden by only a foot of water, a literal minefield in which one must navigate by sight if you wish to pass.

Stephanie, on the helm.

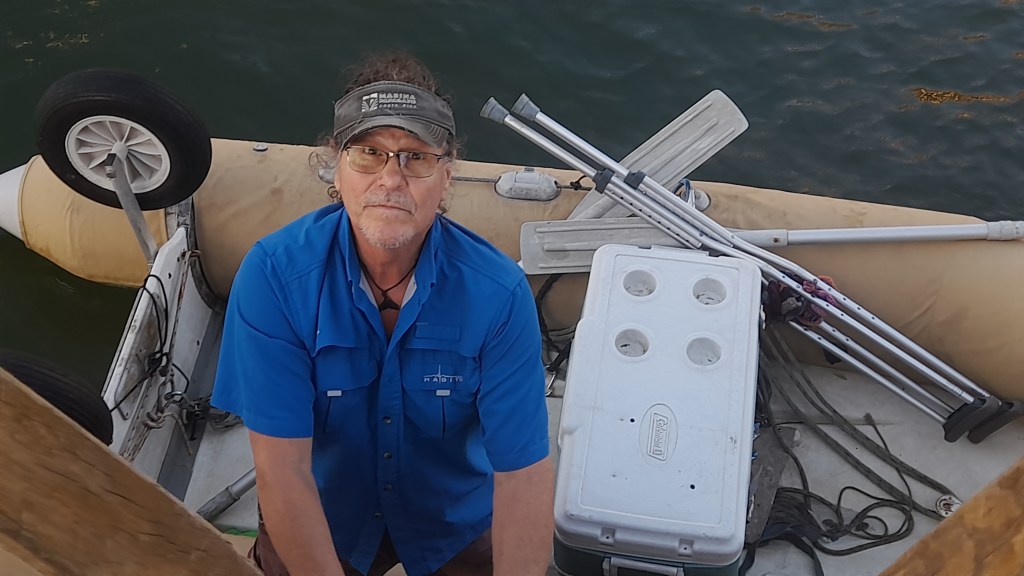

Maiatla was tied to our friend’s dock in Placentia Belize, our crew of Marina and Adriane had departed the boat and were winging their way back to the great white north; not a place I want to be in March. Stephanie, Adriane’s daughter and my sailing apprentice, had later flights to take her back to work in the hills of Mexico where she was employed as a Geologist. We had three more days before she had to depart so we decide to head up the coast to find a place to scuba dive. After diving the Great Blue Hole the week previous, most anywhere would likely be a disappointment, but we were game to try.

We cast off early and once clear of the Placentia cut we hoisted the sails and made our way over to Lark Cay where we hoped to find a spot to dive. We had a grand light air sail as we tacked our way up wind but when closing in upon the Lark Cay, the wind turned fickle so down came the sails as the motored was fired up.

Nestled amongst a handful of Mangrove islands we dropped the hook and prepared to dive as we found a likely looking spot. After donning our gear we dove to find bottom at 70 feet. We worked our way into the shallows towards the reef. By all accounts, it was a dismal lunar seascape with scattered coral bits and few fish. The highlight was spotting a lone lobster under a coral head.

Heading out for a dive

I made an attempt to invite the little guy for dinner but he declined my invitation. Back aboard Maiatla, Stephanie seemed to have enjoyed the dive despite being less than remarkable. I was still hopeful of showing her something spectacular so we wasted no time in pulling anchor and headed north.

The wind had filled back in so under the headsail and mizzen, Jib and Jigger as we call it, we had another great sail. As we tacked up wind we came upon one of the many islands in the vicinity. Crawl Island is a ragged shaped mangrove covered island.

On its west end there were a few thatched roof houses and what looked like a small resort. But what caught my eye was what appeared to be a very large sailboat, perhaps 90 feet long or more. As we closed in on the island and through the binoculars, we saw what appeared to be a large sailing vessel in distress, canted over on a sharp angle with tattered sails flapping in the breeze. It was a shipwreck and a recent one at that.

The Super yacht MAS TAZ with Maiatla anchored in the back ground on a later visit.

“Wow that looks so interesting,” Stephanie said as she studied the wreck through the binoculars. “I’m going to get my big camera” she said as she dropped below. We sailed in as close as we dared before veering westward around the tip of the island. My research sometime later would reveal that the wreck before us was the super yacht, Mas Tas, out of Texas. 28 meters long and had sunk here in 2022.

Sails in tatters, a forlorn looking vessel.

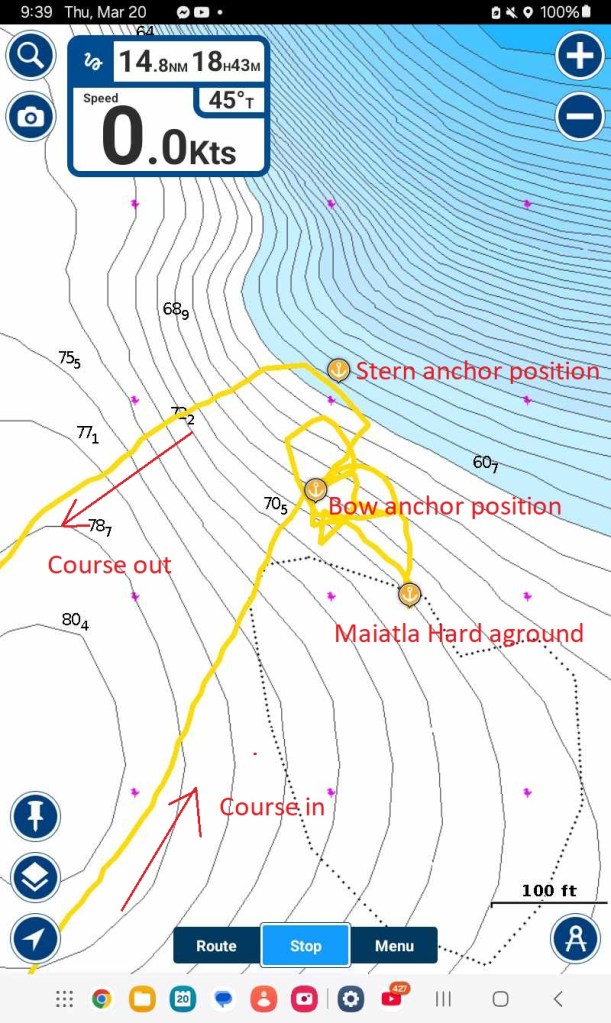

We were still speculating on the ships likely demise when I suddenly noticed the water shoaling, and fast. The bottom had risen from over 50 feet up to less than 10feet in a couple of boat lengths. A quick check of the Navionics chart indicted that it should still be over 50 feet of water beneath us. Charts show the theoretical, the depth sounder shows reality.

Abruptly we made a course change to head beck the way we had come. After several minutes I attempted to resume our original heading but almost immediately we found ourselves in even shallower water with less than a couple of feet below Maiatla’ s keel.

Crawl island- Maiatla drone shot shows the dangerous banks that extends to the east.

We made another abrupt course change but this time we swung well wide of the western end of the island. Apparently there is a shallow bank that extends outward from the island for almost a mile and surprisingly the charts failed to mention this.

“Wow that was scary”, Stephanie said once we were clear of the bank. “That’s probably why that ship was wrecked,” she then added, “do you think seeing it was a bad omen?”

I’m not the superstitious type so I quickly dismissed the notion, but perhaps too quickly. As the wreck fell behind the point, we sailed onward to our planned anchorage for the night. It was getting late, about 3 o’clock and I suggested that by the time we get in it would be too late for another dive, but we could try in the morning.

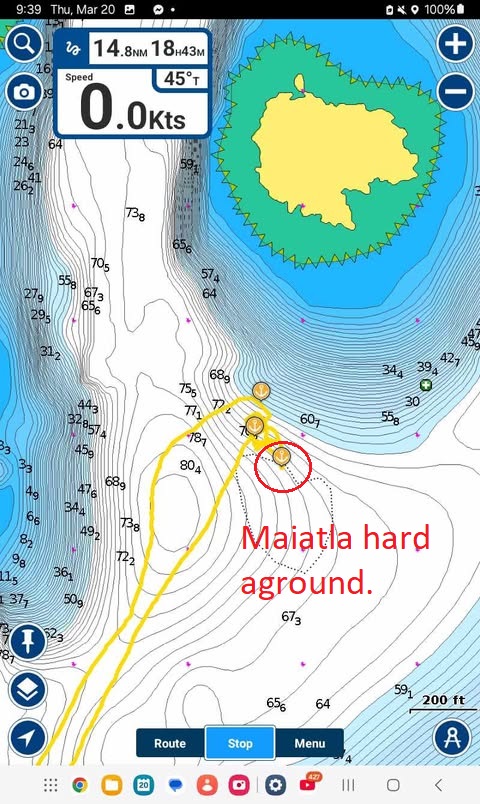

Our destination was Northwest Cay with its almost entirely landlocked lagoon. A perfect anchorage as it was surrounded by islets and reefs. It would be a bit tricky but once in we would be safe from the fiercest of night gales. Still under jib and jigger with Stephanie at the helm, I handed the sheets as we tacked for the entrance. With one eye always trained on the chart plotter we closed in on a tiny island. At about 500 foot distance, we initiated a tack which would send us back across the channel. No sooner had I sheeted in the big headsail, Stephanie called out. “Andy I see the bottom!”

As I glanced over the side I was horrified to see weed patches just below the surface. Before we could react, Maiatla ground to a dead stop. Quickly I let loose the jib sheet and furled the sail. I ran the length of Maiatla to see how much trouble we were in. The bank appeared to consist of soft sand and weed, and it was shallow. I estimated that up to 2 feet of Maiatla’s great keel was buried in the bank. I then called on Stephanie to start the engine and give it full reveres. After a few minutes I called out, “I think we are moving” Stephanie’s response after looking over the side was, “I don’t think so Andy, I’m still looking at the same patch of weeds.” Ok, it may have been wishful thinking on my part. “Stephanie is the tide rising or falling? She checked her watch and I did not like her answer.

The realization that we were in quite a predicament quickly set it. We were fast on a bank, a long way from any potential help and the sun was beginning to set and the tide was falling. On the bright side, the bottom was soft, no coral and the boat was not damaged and the wind and waves was dropping for the night.

Stephanie, who had never experienced something like this was scared, I could tell by the tenor of her voice. I did my best to relieve some of her anxiety by stating that neither us nor the boat is in any real danger and that we would get her off.

She asked how and half-jokingly I said. “We can always wave down a passing pang and ask for a tow.” My remark did not help, in fact I think it did the opposite in giving my apprentice a sense of hopelessness in us helping ourselves.

Looking off the stern I could see the dark blue of deep water and leading back to it was the grove Maiatla excavated when we plowed into the bank. A sight that brought me hope.

We would have to kedge ourselves off. “Kedging off a bank” refers to the nautical technique of using a kedge anchor and line to pull a grounded or stuck vessel off a sandbank or other obstruction by hauling on the anchor cable. Decades ago, I had anticipated such an event and had worked out a plan and fortunately, I have never needed to perform the maneuver, until now.

With Stephanie’s help, I loaded the big Danforth that I use as a stern anchor, into the dinghy. We dug the spare anchor road and chain out of the locker and I went about setting the anchor as far off the stern as the length would permit.

Back aboard, I wrapped the rode around the portside primary winch and heaved the line tight. As Stephanie throttled up in reverse, I cranked on the winch. With the anchor rode bar-tight as it attempted to pull us astern and engine at full throttle, it quickly became obvious that we were not moving. “What now?” Stephanie asked dejectedly as she throttled down.

“More power is what we need,” I said. With that, I went forward to release the bow anchor. Back in the dinghy, Stephanie fed me chain as I drove the big CQR anchor out into deep water off the stern.

Once again I cranked on the winch as Stephanie worked the throttle and the anchor windless button on the consol. The first few pushes of the button did little more than stall the 1000 lbs. anchor windless. But after several attempts, I noticed I was finally able to crank in a foot or two of the stern anchor. The bow winch would retract a few feet of chain before stalling once more. We repeated the process over about 20 minutes. Suddenly the bow began to swing around as the boat made some sternway. The sky had fallen completely dark by the time Maiatla slid off of the bank and back into deep water. Stephanie emitted a cheerful laugh. We were off, but we still had a lot of work ahead of us.

Clearly visible from the air, the bank was uncharted on my Navionics program.

Night had engulfed the seascape with the stars filling the moonless sky. Stephanie was concerned because were still preciously near the bank. “Don’t worry,” I offered, “we have two big anchors out in deep water and we are fine”. In fact, it took over an hour to retrieve both the anchors as they were so well buried into the bottom that neither wanted to come up. As the last anchor came aboard, Stephanie skillfully steered Maiatla on a reciprocal course, following original path in.

We took a wide swing around the western end of the island then turned for shore, creeping in under the guidance of the chart plotter and radar, (again, one theoretical the other actual) until finding 30 feet of water where we dropped the anchor for the night. With the hook down we poured a couple of stiff drinks to celebrate.

I later examined the recorded chart plotter and I was amazed to see that at the very spot where we had run hard aground, the plotter claimed that we still had 70 feet of water under and all around us. The only indication of an issues was a tiny heart shaped dashed line which was hardly noticeable. Placing the cursor atop the line, only a single word appeared which read “Obstruction.” I have seen many such dashed lines on the charts here but none have ever represented a problem before. In Belize, the prudent mariner must view nautical charts with some degree of suspicion and whenever possible, travel with the sun high and behind you with a good lookout on the bow to avoid such, “Obstruction.”

Was sighting the wreck a bad omen? Perhaps. But if so, perhaps the massive shooting star that we momentarily paused to witness during our struggle, was a good omen, a sign that all would be well.

A sailor is born!.

The apprentice, under a baptism of fire, passed her final exam.